My friend Cait and I have been exchanging zeros. I posted a screenshot of my newly empty Gmail inbox, and challenged her to do the same, and she did. Now we’re competing to get to zero as often as possible.

My friend Cait and I have been exchanging zeros. I posted a screenshot of my newly empty Gmail inbox, and challenged her to do the same, and she did. Now we’re competing to get to zero as often as possible.

Email has become almost a breeze for me (after struggling with it for years) due to a discovery I made during my extreme decluttering campaign: having zero clutter is an entirely different experience than having a little clutter. The psychological effect of reducing any type of mess to zero is profound. It feels like a noisy fan has shut off.

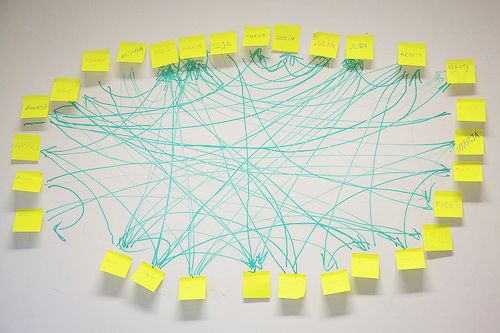

Now I love the feeling of being at zero, and I never want to be far from it. Every neglected possession, unanswered email or open browser tab is like a little hook in your brain. There isn’t a huge difference in how it feels to have six of these hooks in your brain versus having eighty, but there is a vast difference between having some and having zero.

The decluttering post was an international mega-hit— 8,800 12,000 Facebook Likes and counting—which surprised me initially because it seems so pedestrian: arranging items in containers and tossing ugly clothes. But I think most people realize that it’s not really about beautifying your shelves. It’s about turning your home into a better habitat for the mind, one that minimizes the abandoned, the unfinished, and the out-of-place—and creating a lifestyle with fewer “mental fishhooks” snagging your attention.

Whatever is normal to us becomes invisible, no matter how counterproductive, and we’ve simply become accustomed to tracking too many ongoing concerns in our heads.